Tesla’s $25,000 car means tossing out the 100-year-old assembly line

Tesla has a plan to fend off cheaper competition from China with a $25,000 electric car. But first it has to overhaul a 100-year-old manufacturing process pioneered by Henry Ford.

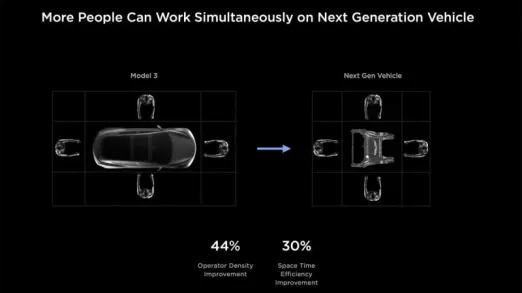

The company is moving to what it calls an “unboxed” approach, which is more like building Legos than a traditional production line. Instead of a large, rectangular car moving along a linear conveyer belt, parts are assembled simultaneously in dedicated areas and then the subassemblies are all put together at the end. Tesla says the change could reduce manufacturing footprints by more than 40%, allowing the carmaker to build future plants far faster and at less expense.

If the new assembly process is successful, Tesla says it can slash production costs in half. That will be key to delivering a cheap enough car to stoke demand that’s slowed of late and pressured the electric-car maker’s stock price. Tesla shares are down 29% so far this year, compared to a 10% increase in the S&P 500 during the same period.

“If we’re going to scale the way we want to do, we have to rethink manufacturing again,” Lars Moravy, Tesla’s vice president of vehicle engineering, said during the company’s March 2023 investor day.

The problem is that investors haven’t heard many details about how Tesla has progressed with the idea since then, even as Chinese automakers have slashed costs and Detroit carmakers have refocused their efforts on cheaper models, as well.

On the company’s most recent earnings call in January, Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk stuck to generalities, saying only that Tesla was “very far along” on making a cheaper car, which is slated to start production at the end of next year. While he mentioned the new “revolutionary manufacturing system,” calling it “far more advanced than any automotive manufacturing system in the world, by a significant margin,” he didn’t elaborate.

Musk is notorious for missing deadlines, and some on Wall Street are dubious that Musk can meet his already-delayed timeline — he first teased a $25,000 EV way back in 2020 — much less the savings targets. Tesla’s method is unproven, and may come with its own inefficiencies and risks. A recent analysis by Bloomberg Intelligence estimated that the new modular manufacturing process would cut costs by 33% — not half.

Tesla didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In the absence of details, some people are taking it upon themselves to figure out how well the system might work. Mathew Vachaparampil, CEO of Caresoft, an engineering and automotive benchmarking firm, said his company’s engineers spent 200,000 hours building a digital replica of Tesla’s unboxed platform. They found that Musk’s ambitions are technically possible, and Vachaparampil said they would make “huge financial sense” — if achieved.

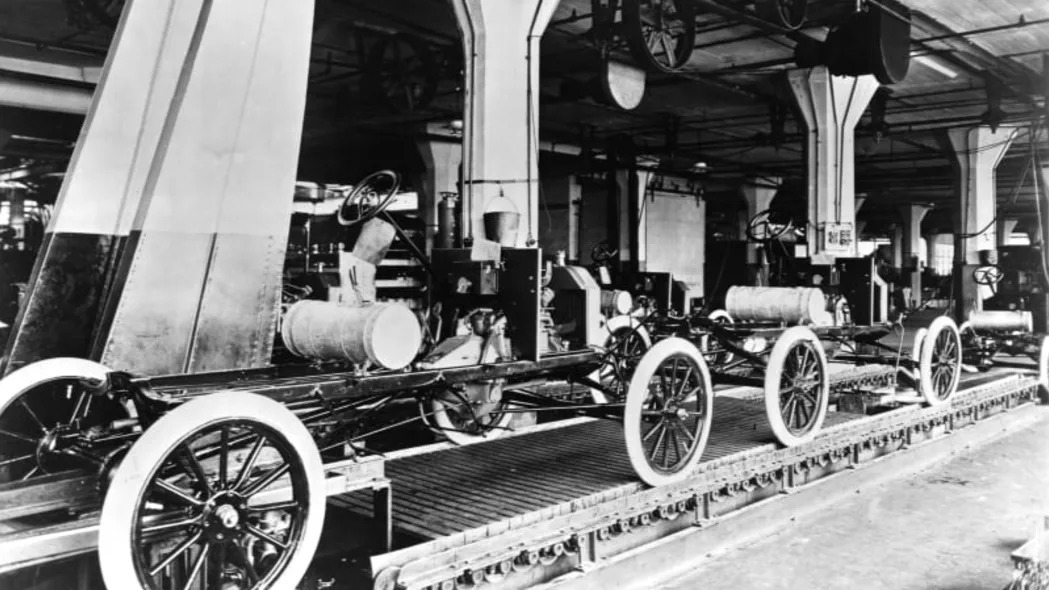

Ford’s Highland Park plant, birthplace of the factory assembly line. (Ford)

Ford’s legacy

Most mass-market automakers still largely adhere to the same basic setup used by Henry Ford in 1913 to make the Model T:

- Stamped panels are put together in a framing station and welded into a rectangular, boxed-shaped car.

- Doors are put on.

- The vehicle then goes through the paint shop — either dipped into a big vat, or sprayed and dried in large ovens.

- The freshly painted doors are then taken off.

- Wiring and an engine or motors are dropped in along a winding assembly line.

- Seats and other parts of the interior are put in, and then glass windshields and windows are added.

- The doors come back on right before a final inspection.

That process, Tesla executives say, is rife with inefficiencies. Moving a car-sized “box” through a factory (as shown at the top of this article) takes up a lot of space. Painting an entire machine, instead of just the panels that need it, takes time and wastes energy. And working off of a hulking frame means only a few people can assemble their parts at a given time.

The unboxed method doesn’t require a big skeleton of a machine to move through a factory. Instead, splitting off into small groups, workers labor on various components of a vehicle simultaneously before it comes together at a single point in final assembly.

The potential cost savings are substantial, according to Vachaparampil. Caresoft sees at least a 50% reduction in paint-shop investment in new factories alone.

Paint has long been the most expensive part of any auto plant: The high heat required for automotive paint is energy intensive, and there are strict emissions requirements. The throughput of the paint shop largely determines a plant’s total output, according to auto plant experts.

A typical car body is 6 feet (1.8 meters) wide and 15 feet long. Instead of sending the entire rectangular body through a paint shop, Tesla’s unboxed process will paint the individual panels before the car is assembled.

Untested method

The unboxed method has plenty of risks of its own, mainly that it’s unproven and requires shifting to a new assembly process, which could lead to production delays.

But it’s not the first time Tesla has made significant changes to improve long-held manufacturing practices.

With its Model Y, instead of stamping various pieces of the car, Tesla turned to die-casting machine presses to “gigacast” — or create giant molds — of the front and rear of the vehicle. That eliminated the need for hundreds of parts and welds.

Other U.S. automakers are also working to fend off the competitive threat posed by Chinese cars. Ford Motor Co., for example, is exploring a compact EV that would use a cheaper battery.

“The concern is that the lower end of the automotive market isn’t currently being served by electric vehicles, but they will be served by China if U.S.. companies can’t cut costs,” said Susan Helper, a professor of economics at Case Western University, who recently served as a senior adviser for industrial strategy at the White House Office of Management and Budget.

But Musk’s company has an edge over longtime automakers in adapting to novel, potentially cheaper manufacturing techniques. Tesla’s factories are newer than most, and some aren’t even under construction yet, so it can more easily and cheaply tailor its facilities to run on cutting-edge manufacturing methods.

That doesn’t mean it’s easy. The company has warned investors that it’s “between two major growth waves” as demand for the Model 3 and Y — both of which have been out for years — tops out. Tesla delivered 1.8 million cars last year, but aims to deliver 20 million cars by 2030. To do that, it will need much cheaper cars.